So last week we spent some time looking at what the soul is, and Amber, in her discussion about the intellect, referenced the five powers of the soul. I thought this might be a useful point to pick up our general discussion, allowing us to understand the human soul in an increasingly deep manner through refining our understanding of soul generally. For reference, much of this discussion will be particularly drawing from Aristotle’s De Anima 413a11-418a25 (or Book 2 Ch 2-6) and Aquinas’ commentary on that reading.

So having defined soul as “the actuality of a natural body having life potentially” (412a19-20), Aristotle acknowledges that there are many ways we say something is alive: our oak tree is alive so we shouldn’t strip its leaves, the worm is alive so we should be careful not to step on it, the bird is alive so we should be mindful of its nest, the bunny is alive and that’s why the kale is dead now, the chrysalis has a living thing in it so don’t disturb it, the baby in Mama’s tummy is alive, you and I are alive, the car is not alive though, nor the vacuum, nor the clock, nor your picture. There is a line demarcated between the living and non-living things, though at times our technology or the likeness of a non-living thing to a living thing can cause us to fail to distinguish where a given object falls. But that failure to distinguish, as children give a solid case study of, is often due to either mistaking some sort of motion as being a natural or proper motion to the thing, as opposed to accidental due to the artificial form the parts receive, or it is due to mistaking what is alike—a picture of a woman looks like a real woman and a real woman is alive, and the likeness of appearance is what indicates something is alive.

…but it does seem that the way in which my children are alive is not the same way in which an anemone is alive.

And yet, even once we consider living things, it seems natural to ask whether they are alive in the same way. Observation suggests it is right to say that an oak tree, an anemone, a worm, a bunny, a chimp, and my children and I are alive, but it does seem that the way in which my children are alive is not the same way in which an anemone is alive. An anemone has never asked me to read another bedtime story, after all. What this is getting at is it seems there are modes of activity which we recognize as life: the activity of the intellect, the activity of the senses which is the principle of appetitive activity, self-motion as local motion, and self motion as growth/decay.

Of these five modes of life (the sensitive and appetitive being distinct, but the appetitive accompanying sensation in creatures), it helps to see how they are present in actual living beings. So, everything which is alive has the power of growth and decay, which we sometimes call the vegetative power. Plants grow. If you’ve ever had an invasive species attack your yard, you are likely well aware of this mode of life. Also plants die. If you’ve ever tried to grow a vegetable garden, you are likely well aware of this. But if we say they walk, desire, sense, or think, it seems right to say that such language is at the most a metaphor recognizing that the plant has a stimulus in response to some stimuli, but, as we will explore more next week, it’s not clear that we can say a plant is receiving a sensible species in the way things with the sensitive mode of living do.

There’s something it’s like to be a bat (or even an anemone), and we can’t say the same about a tree.

Now consider the sea anemone. These creatures do seem to have more than plants especially insofar as they have a dispersed nervous system. Though some botanists have argued for expanding the definition of a nervous system, such expansion once again appears to be metaphorical, not properly an analogical extension of the name, because plants simply are not conscious in the way animals are of their environment. As Feser helpfully puts it, there’s something it’s like to be a bat (or even an anemone), and we can’t say the same about a tree. Plants have chemical reactions that lead them to turn towards the sun, but at least anyone who isn’t a strict materialist will argue there is an internal psychological experience of feeling sunshine that even anemone’s have (we will get to materialist objections, I promise), but plants do not. Plants might turn towards the sun, but anemones have the experience of sunshine. (Again, we will circle back to this claim for a deeper treatment later on in this series).1

Creatures with the ability to move…seem to be more alive than plants and anemones.

But, to be honest, the life of a sea anemone, and the appetites it possibly has are a rather limited experience of life. Creatures with the ability to move, even in the odd way clams can, seem to be more alive than plants and anemones. (Below see a clam living its best, wonderful life.)

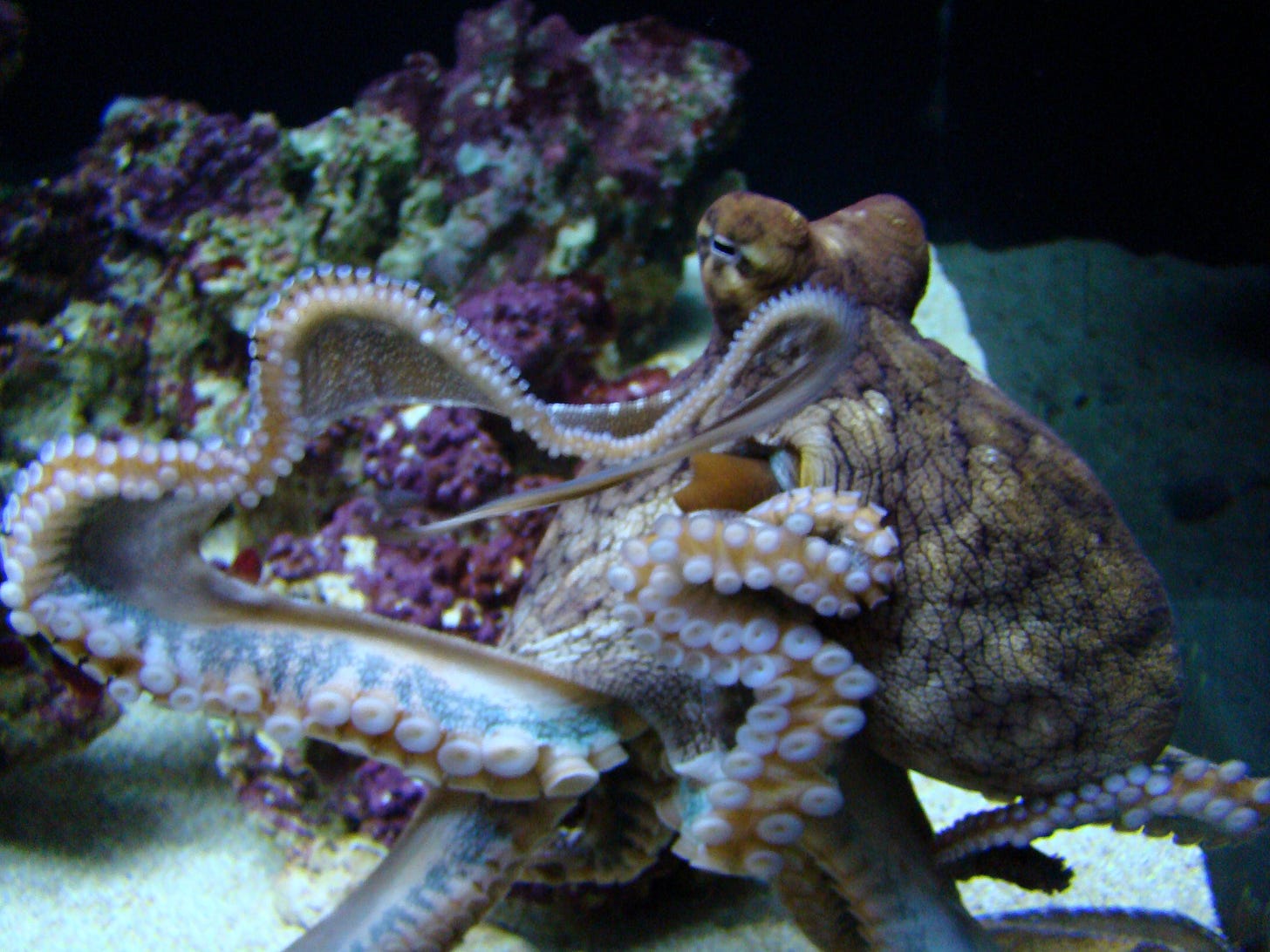

This life is far more obvious in higher animals with both more complex sense powers and appetites and more complex abilities to achieve their appetitive desires. For example, while I would argue about the use of the word intelligence in this article, it is clear from the examples discussed that the octopus is more able to desire and achieve those desires than an anemone is. In part because they can move around and in part because they seem to have more powerful sense organs, the way an octopus experiences the ocean is greater than the way an anemone can. Or, to get on more familiar ground, the way a dog experiences the pleasure of greeting its owner is more lively than the experience of a worm greeting its owner. And if you have to ask why we have pet worms, well, some children might have confused them with snakes.

…even very young children can make jokes and desire to share those jokes with others, and humor requires at least some grasp of a universal.

But even the pleasure a beloved dog has for its owner is not the same as the pleasure a child has for their parents. This is because children can know and love, and be known and loved by, their parents because of their intellectual powers. Children, unlike dogs, are made for communion. See, human persons have sense powers, much like animals do, but we are fundamentally rational animals. We have the intellectual power that allows us to know and love (will) and to abstract that knowledge and love from a particular sensible thing. How this all works is again, a topic I will punt on until a later essay, but for now let it suffice to say this: even very young children can make jokes and desire to share those jokes with others, and humor requires at least some grasp of a universal.

But here we are beginning to run headlong into the question of what are the particulars of the sensitive powers? How is local motion related to those powers? What is the intellect and why do we have it? Or do we have it? Do other creatures? How do we engage the science? And so, rather abruptly at this intellectual cliffhanger, I will say we will address all those, but in the next essay of this series.

But to help with your eager anticipation, I will leave you with this lovely poem about the experience of both of the poet and the dog (the wonderful Mary Oliver’s The Storm):

Now through the white orchard my little dog romps, breaking the new snow with wild feet. Running here running there, excited, hardly able to stop, he leaps, he spins until the white snow is written upon in large, exuberant letters, a long sentence, expressing the pleasures of the body in this world. Oh, I could not have said it better

Part of the problem with the soul is establishing the experience of the natural world in some way so we have a common experience (or at least a reported common experience) to work with here, before we address other topics that are contained in our current exploration but would be better undertaken once we have a bit more foundation to engage those questions seriously. So, bear with the punting for now and we will circle back around.